For this edition of Beyond Casual Observation, Ashley Lynch, owner of Burnaby, BC-based Gingerbreadgirl Post—a versatile post-production studio that specializes in genre film-editing, colour grading and theatrical trailer campaigns—stepped away from a busy schedule to answer a few questions for us. As I've focused on film music, sound effects, foley, and everything else audible in film (this is a music site after all), I've come across points in discussions where exploring the assembly of film helps expand this aural analysis. Ms Lynch's depth of experience in post-production provided both practical and artistic layers to this series. Her work has been seen on Telus Optik, Discovery Channel and A&E, and in film festivals around the world.

BJ Rochinich: Please describe the role of the editor in the creative process, and elaborate on the duties of a colorist.

Ashley Lynch: I'm not the first person to say it, but editing is really the third chance to tell the story. It happens once on the page, again on the set and the final pass is in the edit room. There's a difference between what is idealized on the page and what actually gets created in the camera. I've always seen the editor's job as taking that original spirit of intent for the story and trying to best realize that with the footage created. And the whole time you're also trying to give it that extra push to turn the material into something that truly connects with an audience and transcends.

The best editors operate from a place of both experience and instinct, and when you choose an editor for your project, you're hopefully doing it because you believe their skill and creativity are going to make the project better. I've been lucky enough to work with some fantastic directors who allow me an almost criminal level of freedom when creating the first cut of a film. I always like to tell people that with my edits that what you get isn't going to be exactly what you expect but it will be really special, and hopefully exceed expectations. I'm not afraid to change the pacing, mix shots up, play with time or overlap dialogue if that's what my gut is telling me to do. But I'm also a writer and director myself, so everything always has to be in service of the story. You always have to asking yourself if this is the best or most interesting way to tell this story, and if the answer is "no," you know you have more work to do.

The colourist has two roles, and much like editing, they are both uniquely technical and artistic. The first job of a colourist is to make the movie balanced. Shots need to look like they match even when they were filmed on different days under different lighting conditions. When colour is off, an audience notices it, if only subconsciously, and that's a problem. The second part of the job is to create a look for the film. This is where sometimes it gets tricky, because traditionally it's been the Director of Photography who decides the look of the film and it is achieved in the camera, but in this age of digital cameras shooting RAW and digital colour correction, that's decreasingly become the case, and suddenly the DP and the colourist are in a position where they're both working to create a unified visual look for the film. Some DPs view this relationship as adversarial, but the best ones embrace the collaboration.

BJ Rochinich: Please describe your own unique process when you sit down and prepare to edit.

Ashley Lynch: It's hardly a unique process, but it's one every editor should get in the habit of doing and that's organizing their bins. Setting up your project with detailed organization and maintaining it is the thing that keeps you from pulling your hair out towards the end of the edit process. But after that I just start building. Grab the first scene I have in my possession and start my craft. Some people like to do rough assemblies of a film and then go back to start to refine, but I despise this. The fewer revisions of something I have to do, the better. I always tell people that I don't do rough cuts and the first cut they receive from me is really a fine cut. If something isn't working in an assembly, then it's probably not going to magically get solved by chipping away at the edges. Editing for me is not about dropping down a huge piece of granite and then chiseling away at it until I see what I want. I polish as I go and like to see immediate results.

BJ Rochinich: What software do you use for editing and color grading?

Ashley Lynch: My go-to software is Adobe Premiere for editing and Davinci Resolve for colour grading. But I try not to get too hung up the software because sometimes it's a matter of the situation and who you’re working for. I've edited and colour graded lots of TV that were in completely Avid environments and everything was done inside of Avid Media Composer and Symphony. The principles for editing and colour grading are the same regardless of the software you use, so it's entirely about what allows you to work the quickest. Software is just a tool and 99% of what I do in Premiere can be accomplished in any other software because it's the same basic editing techniques we were using when we cut with actual film.

BJ Rochinich: You have done sound work and been part of the production team. You have worked on short films and mini-series. How important has it been for you to be so versatile?

Ashley Lynch: I hate not knowing how to do a job even if I'm letting someone more skilled than me do it. This mostly comes from my director hat where I feel the best directors know every aspect of filmmaking. David Fincher may not be operating the camera, but he knows how a 50mm lens looks from this angle compared to a 25mm lens. He knows what mics are needed to get the richest dialogue. He knows how online telecine and digital colour grading works and how far he can push it even though someone else is doing that job. This is a great and respectable quality for a director to have, but that by no means should it be limited to just that role. I think most film professionals would benefit greatly from walking a week in another department's shoes. If camera crews spent any time in post, there are certain habits they would change in a heartbeat.

But I'm also constantly trying to grow as an artist. I think the best filmmakers are ones who push themselves further with every project. David Bowie called this going out into the water until your toes can't quite touch the ground, and then you're ready to do something interesting. If I'm not learning a new skill, pushing a boundary, or swimming in an area where I can't touch the ground, then I'm just being stagnant, and that's boring.

The Mythos series is a great example because I had so much footage to choose from and so much freedom. There was a script, but it was mostly voice over that carried us through several dream-logic parable-like nightmares. I've said editing that series was like trying to find the lost city of Hell without a map. I just kept pushing things and pushing things until I got emotionally unsettled by what I had created, and figured if it was disturbing to the editor, then it would certainly be so for an audience. But through that process of discovery, I stumbled onto a few techniques that I've tucked into my toolbelt and used on other films. I'm always most excited when I don't know how I'm going to make something work.

BJ Rochinich: In your years in the profession, what are some aspects about being an editor that have surprised you?

Ashley Lynch: This is going to sound awful, but I'm always surprised at how invisible the editor is. Even with other people in the industry, I don't think there's a lot of understanding just how much control and influence the editor has over a finished film. Yes, ultimately it's the director's film, and a good editor is always trying to tailor it to to the director's sensibilities, but a lot of what we think of when it comes to a director's unique style is coming from the editor. There's a reason filmmakers choose to work with the same team over and over. How much would Martin Scorcese's films resemble his style without Thelma Schoonmaker's editing? And we've already seen a difference in Quentin Tarantino's films after the death of Sally Menke. More and more, you start to realize how much of what we call "style" or "vision" is a collective team effort and not the singular realization of one person. Basically being an editor for long enough has obliterated the auteur theory for me.

Check Ashley’s profile out on IMDB and take a look at her 2016 reel:

Normally this column is written about a single film, however, because Ms. Lynch was the editor on a Batman-related fan film called Nightwing:The Darkest Knight I want to say a few words about that piece in addition to the primary film.The Darkest Knight makes use of many DC characters in Batman’s world to craft a rather involved story whose moving pieces create abundant character conflicts that develop the story and the characters well for this particular story. The fights are pleasing, with a combination of good choreography and a lack of disorienting camera work; after all, we want to see Nightwing fight. The score is serious, and the drama is heavy.

Here is The Darkest Knight in its entirety:

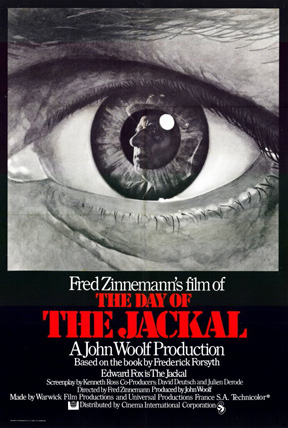

To choose a film for this edition of BCO, I browsed lists of awards winners for best film editing. I considered watching Don’t Look Now, Marathon Man, and Blue Thunder. I mention those now as recommendations, and hints at potential featured films in this column, however I chose The Day of the Jackal, which won many awards in 1974 for Mr. Ralph Kemplen’s film editing work. The glow of editing as a story-telling device shines bright in The Day of the Jackal. The movie is long, it's plot assembly is interesting, and the precision with which small actions composite scenes is hypnotic. A heavy tension slowly developed throughout the film's first two hours unleashes an exciting final act as our characters race to the finish line.

I find it generally interesting to watch a film that essentially focuses on two characters, battling in parallel timelines, forging the inevitable confrontation. This device is where Kemplen's editing soars, creating a tense, riveting story of the offender and the pursuer. Kemplen's editing creates character opposition despite a minimal face-to-face confrontation. The worlds of our support characters weave into the plot, providing depth to a complex and dense story. These characters, who develop organically in the story, are collateral elements to our main characters, and help push the story forward rather than convolute it. The final act is highlighted by a final moments that bring a release of the tension built throughout. I sat back into my chair not realizing that I had tensed up during the film. The epilogue is rather concise, and absolutely effective and left me pondering a moment past the final shot, a hallmark of 70s cinema.

Like Bullitt or The Last Good Friday, Jackal also has a historical value in its geographical photography, in addition to the actual real-world influences upon the story. There’s not a lot to say about music in the picture; I want to say there is not much music at all as I can not recall impactful scored moments. There is plenty of interesting audio in the film: the small sounds, the explosive sounds, and the dialogue. In a scene where the antagonist tests out a new weapon, the sound of the adjustments to the gun’s sights, the ferocity of the shot, and the decision to leave the background of the scene eerily quiet are intoxicating, and effectively makes the weapon a character. This film, and similarly paced films look inwardly and find the drone, the atmosphere, and the space surrounding our experiences that arguably is as valuable to our experiences as the moments of action. While editing picture is obviously a visual element, it can have a profound impact on the soundtrack. The question of adding music can be answered by mirroring the pace, as well as juxtaposing it with a piece whose pace is opposite that of the action, which, on the surface seems to be completely contrary to the sequence. Whatever the mood, whatever the pace, picture editing is also a rhythmic art, and conjoins with the actual soundtrack making it inherently musical.

I am very interested in hearing readers' responses as to finding parallels among favorite films, to editors, to composers.

Thank you for reading, and always stay through the credits.